William Butterfield

Nothing Permitted But What Has Been Foreseen

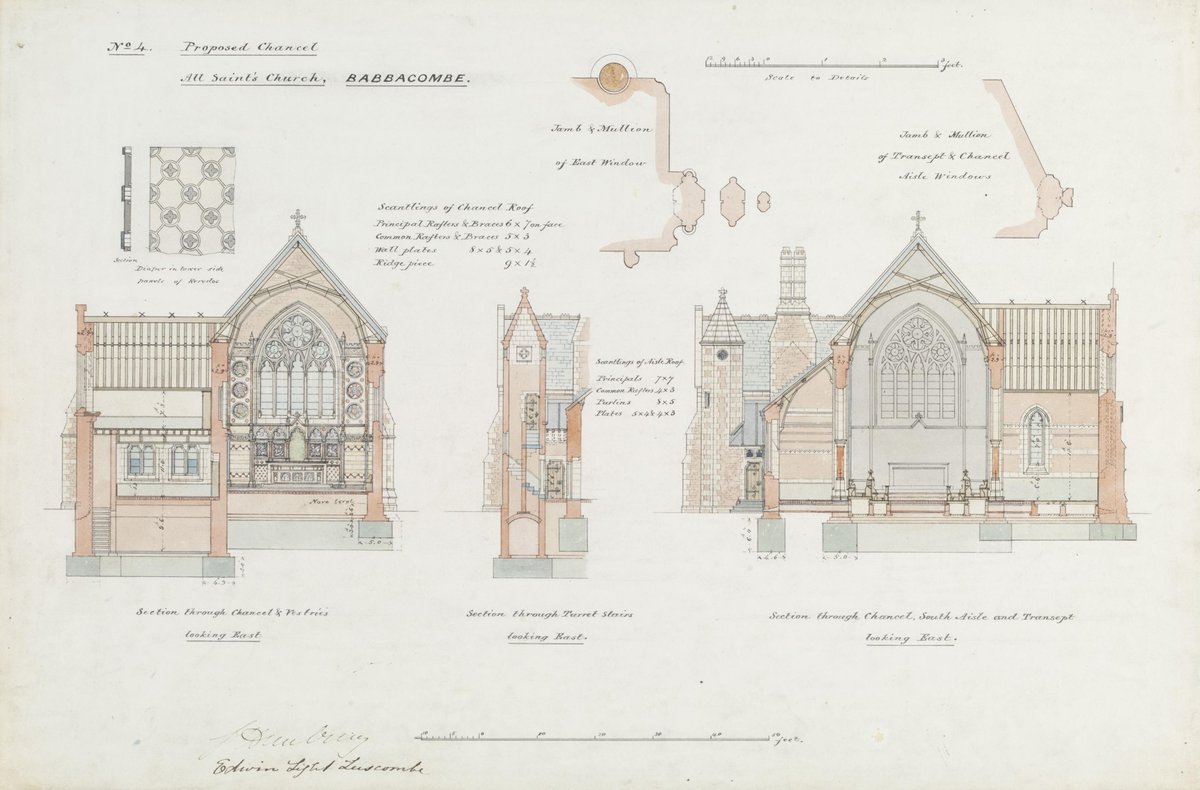

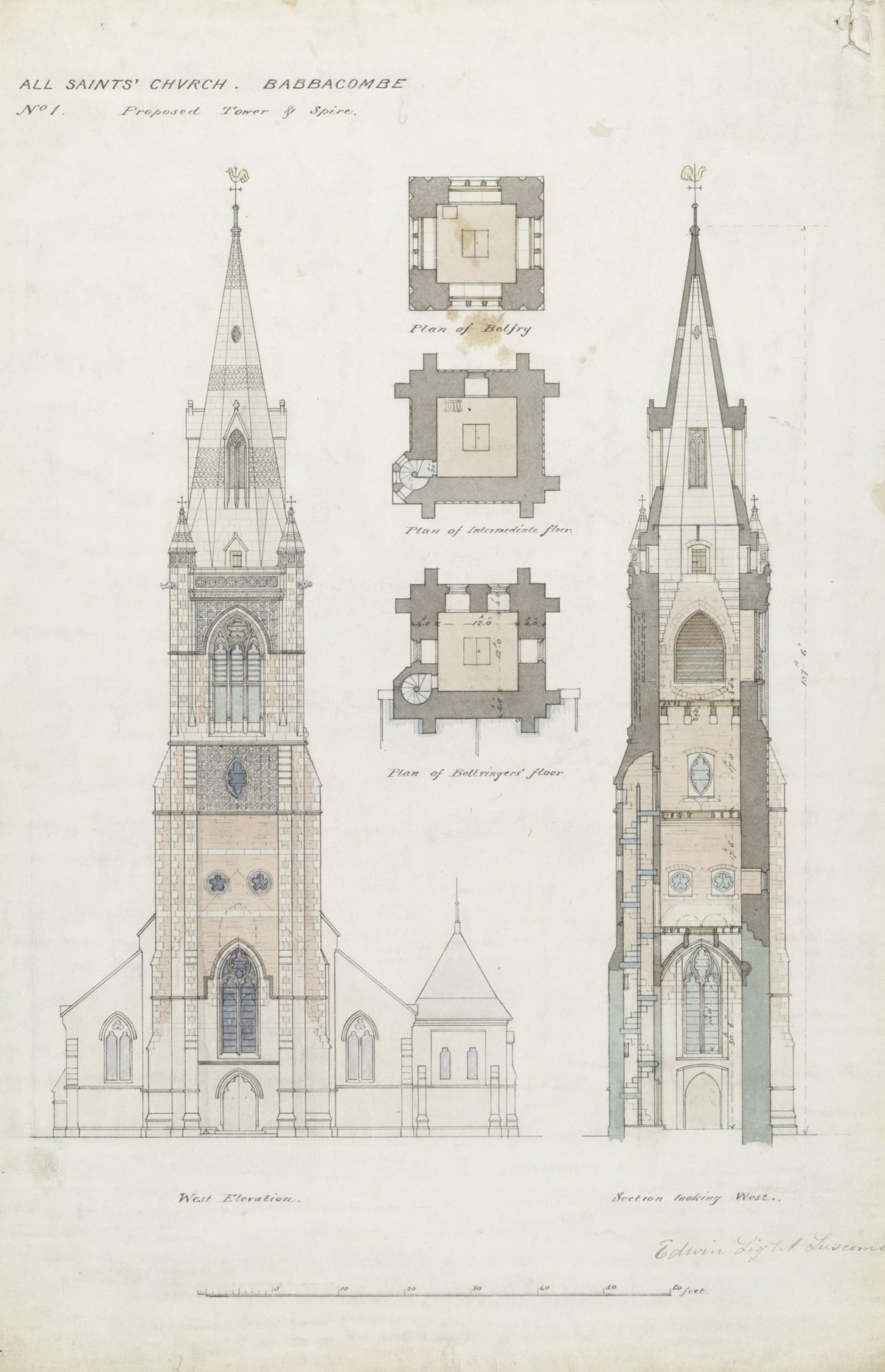

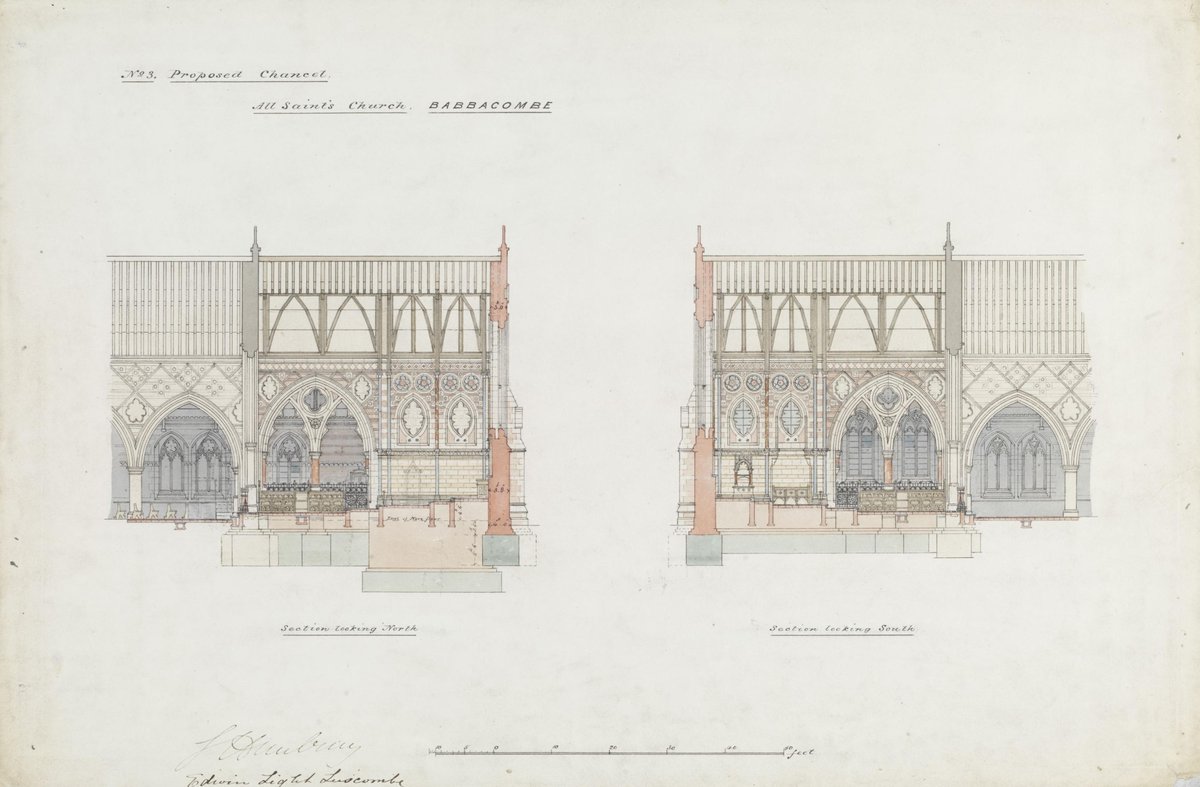

William Butterfield eschewed the illustrative perspective, preferring instead to develop even his studies as contract drawings that would serve three tasks: as presentations through which a project could be comprehended, as instructions from which his contractors and clients could not swerve, and as precise statements of specification on which the builder’s tender could be based, signed and held to. They are prepared on thick stock in a format and media that allows ready shipping and handling, as they move back and forth between studio, client, builder, and the public agencies who funded or approved. Perhaps as a result he became famous both for his intransigence – even the proudest clients (quite proudly) referring to themselves as his slaves – and for the astonishing economy and punctuality with which he delivered the work.

His favoured presentation system was based on a set of volumetric sections in which a layer of shadowy one-point perspective behind the plane could reveal the essence of what lay beyond. His methods render the contract drawings completely in character with the intention of the built work, in their use of colour and line, in their uniformly crafted calligraphy, and in their two-dimensional synopsis of the underlying spatial logic. At the same time, Butterfield gave unrivalled attention to how his drawings were laid out on a page and how they would communicate his first principle of design: that the building be seen and conceived as a whole and built with a unified approach to construction, proportion and detail. Notes on the measurements of floors and roofs are precisely written in the smallest hand, in a way that extends the lines of the divisions they specify. And in their precise distinction of materials, joints and structure, Butterfield shows the same delight in structural anatomy on the drawn sheet as a builder enjoys on the site, and as much passion for materials rendered on the page as a mason feels for them in the quarry or a carpenter at the lumberyard. In his drawings it is as if, in the words of Halsey Ricardo (who knew him well and captured some of the finest of his presentations), he had discovered and tested the bearings of each of the varied elements himself, and ‘mingled them with a lover’s fondness… As far as a man may go, who does not actually hew the stone, lay the bricks, and shape the timbers, he had his hand on the work. There is nothing permitted but what has been foreseen.’