One Thing Leads to Another

Architecture rarely results from a singular eureka moment or a spontaneous act of genius. The myth of the napkin sketch is precisely a myth. The lucidity it suggests is essential, but it is seldom instantaneous or hermetic. It comes from work. In architecture, this work is of a special kind, requiring concentrated inquiry into the possibilities of a project: a continuous critique of ideas and assumptions in pursuit of conceptual, spatial and tectonic clarity.

Conversely, much contemporary practice has an odd relationship with iterative processes. Rather than the outcomes of curiosity, options have a tendency towards desperation or deceit. At times, they seem to serve as a kind of rudderless pin-the-tail-to-the-donkey substitute for productive ideas. At others, they come into play when it is perceived that a third-party need to be convinced that other trajectories have been considered; taking the form of a cynical prediction of failures to validate a preferred direction.

This is perhaps curious given that, objectively speaking, many design decisions are not entirely rational anyway. Coherence – the internal logic of a project – is achieved through the legibility and robustness of the framework of ideas that guide the decision-making process. Within such a framework there are many possible outcomes, ranging from the specific nuances of a strategic direction to the formal, spatial or material variations possible within a given strategy. Artistry lies in the skill and purposefulness with which choices and judgements are made within, and in support of, this framework of ideas.

Iteration and architectural rigour are therefore inseparable. We have all felt the anaemia of a project that has come about through under-interrogated actions: where an architectural veneer is thinly stretched over idea-free choices. Repetitive activity plays a particular role in this interrogation. Flimsy preconceptions begin to dissipate under repeat scrutiny; essentiality and significance slowly aggregate with each cycle of critical engagement.

Drawing offers a number of trajectories for this kind of work, ranging from the focussed turning over of rough propositions in search of intentionality, to the sequential and methodical exploration of possibilities within an already established conceptual framework. The dense collection of studies produced by James Gowan for the Expandable House (1956) and the taut thematic variations set out in John Hejduk’s Thee Projects (1969) illustrate two such paradigms, through distinct but overlapping attitudes towards the reciprocity between iteration and rigour.

Searching

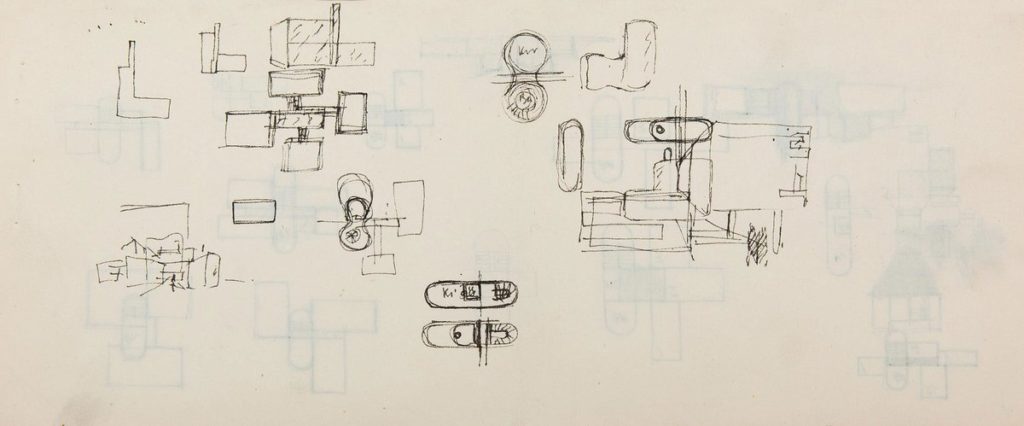

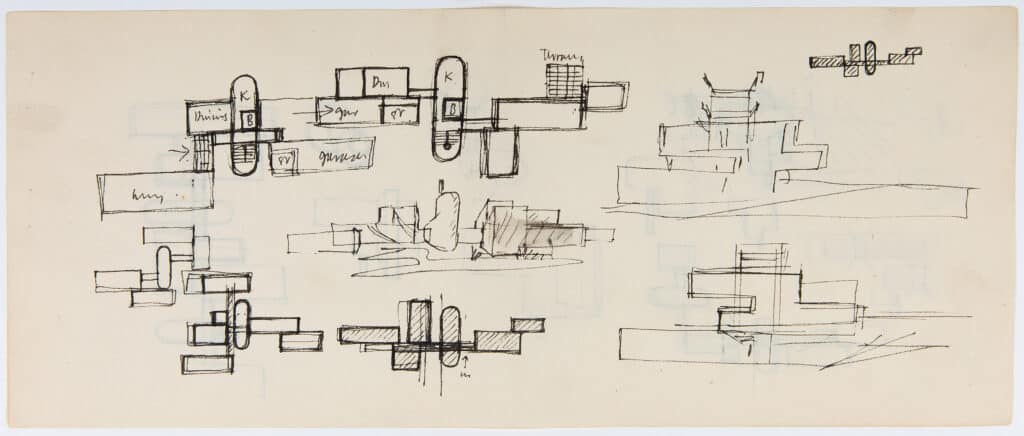

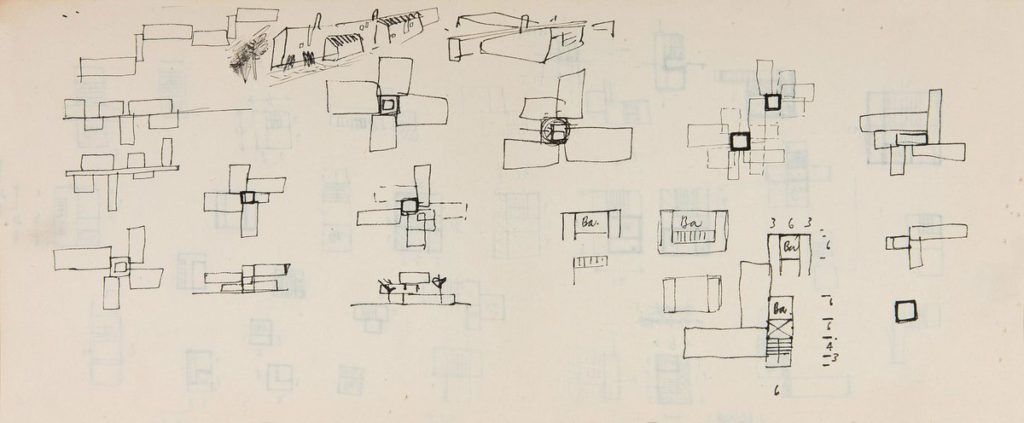

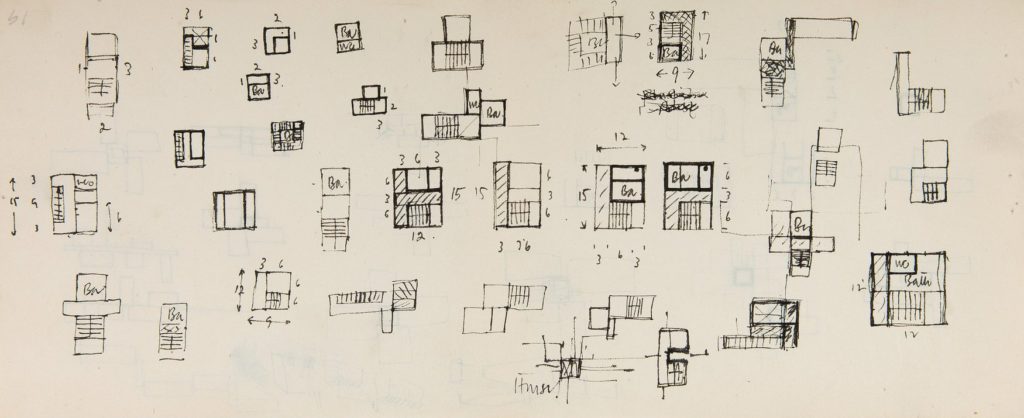

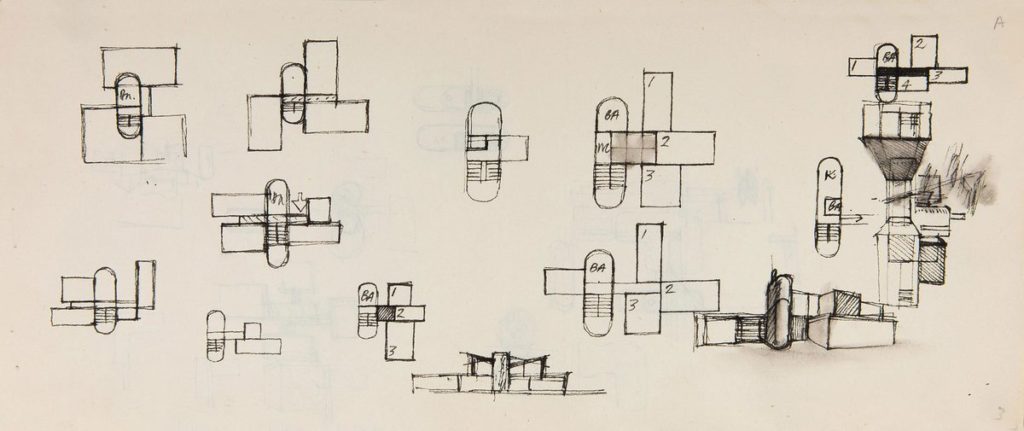

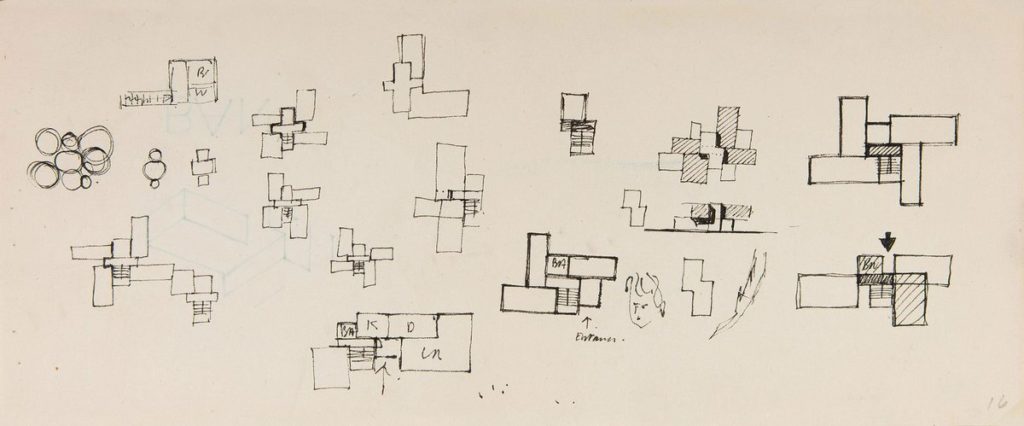

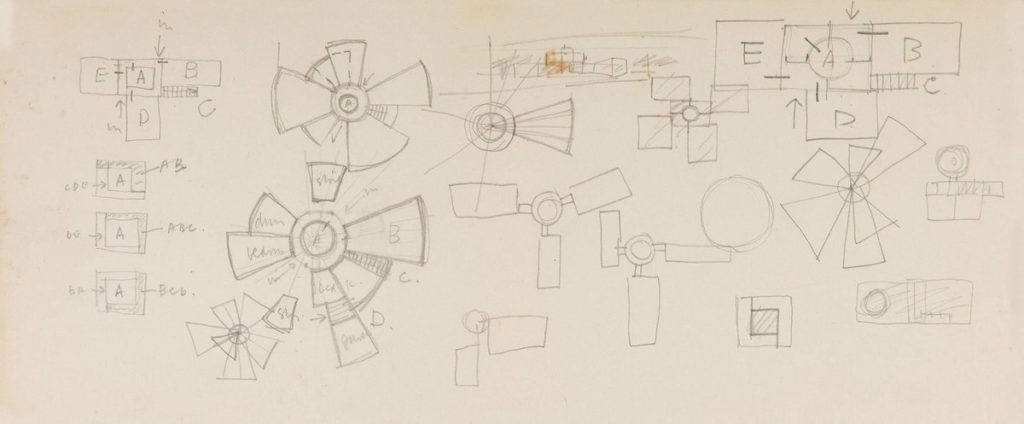

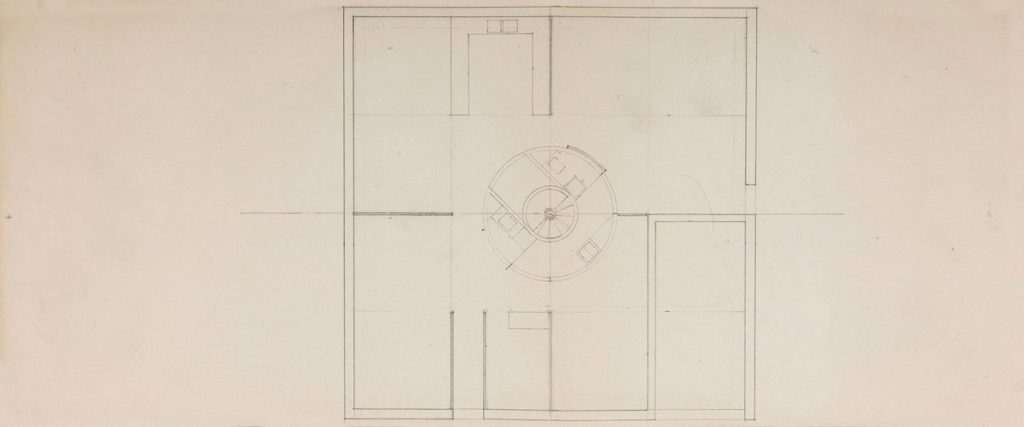

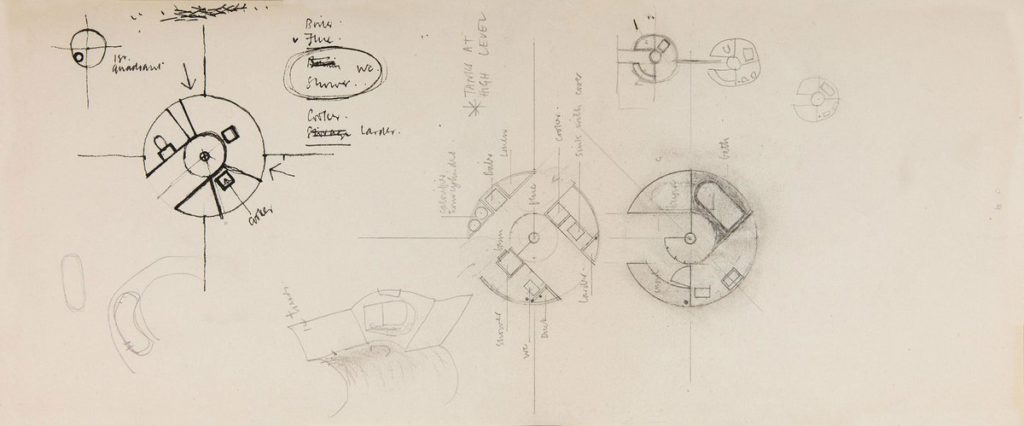

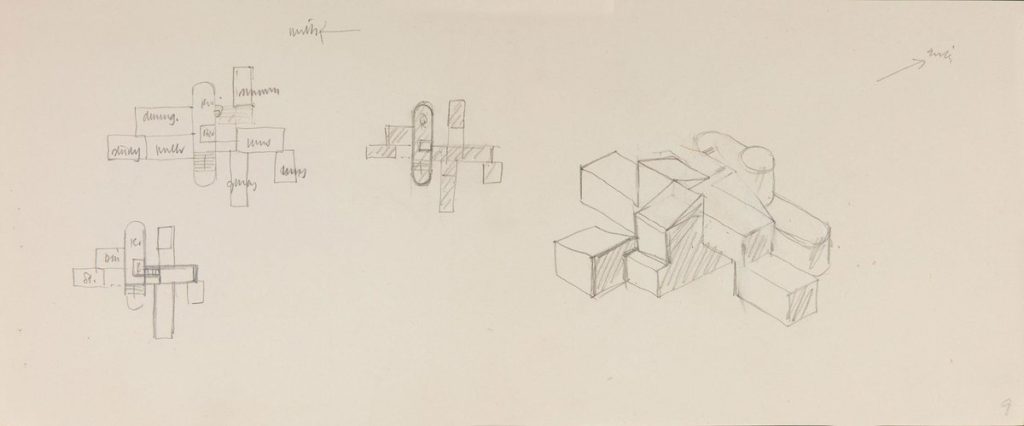

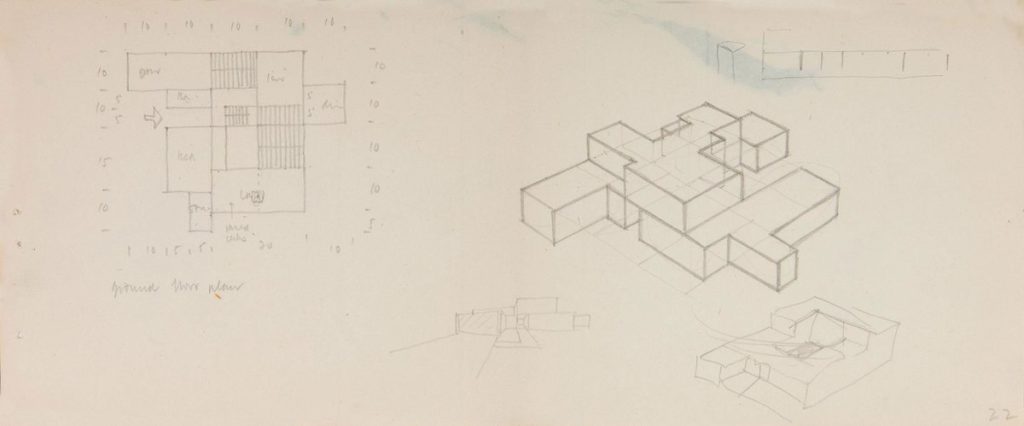

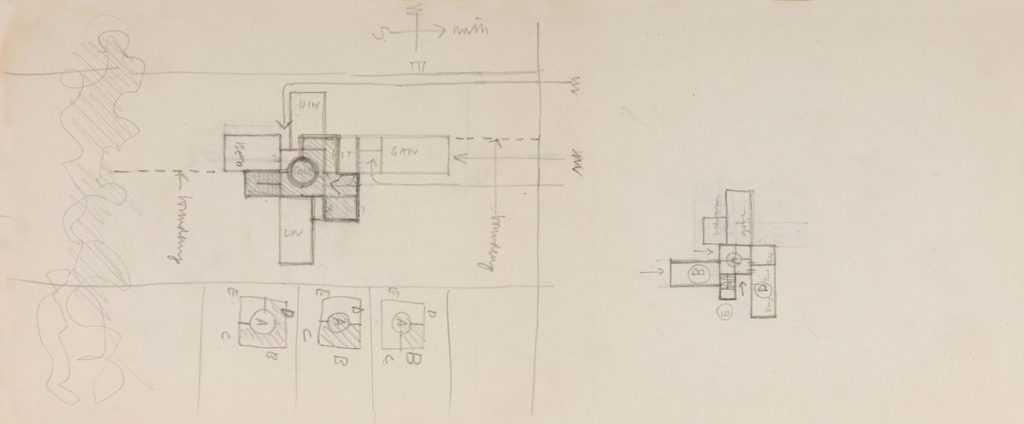

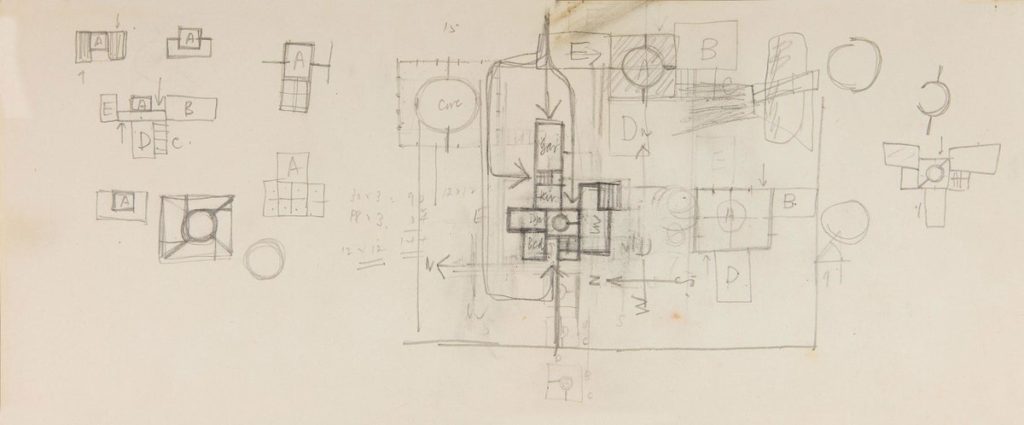

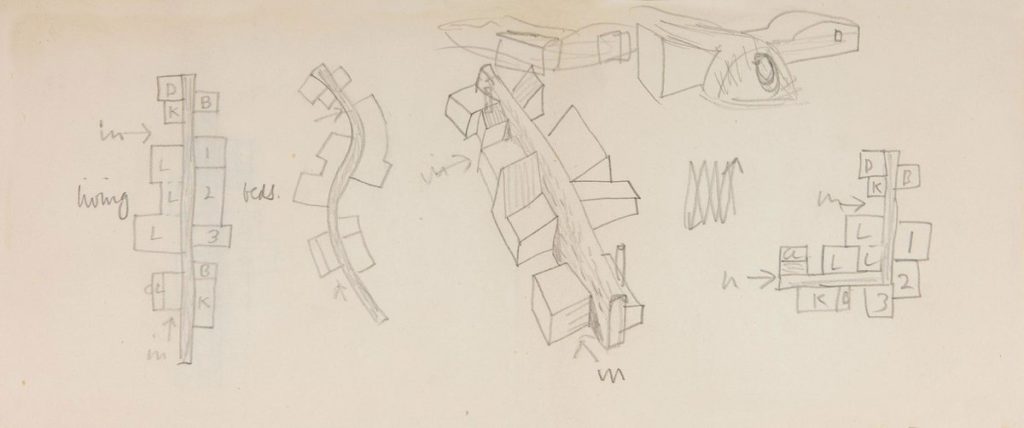

Gowan’s sketchbook for the Expandable House competition (undertaken in partnership with James Stirling) reveals an intense preoccupation with the relationship between circulation, rooms and form. Specifically, this preoccupation appears to focus on the development of circulation as figure, and the potential range of volume configurations that might be supported by variations of this figure.

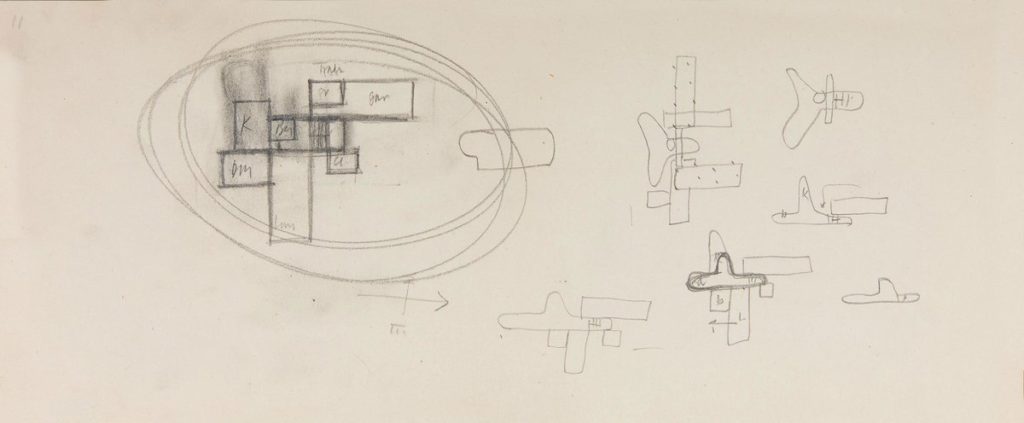

Unfolding over twenty-eight sides of unbound paper, the sketches include perspective, isometric and elevation studies of formal composition; occasional, tentative outline sections; an extreme number of plan diagrams; and at least one face. Of these, the approximately 175 small plan studies are the most intriguing in both their obsessive repetition and the breadth of configurations explored. The origin of Stirling and Gowan’s idea is evident in the various incomplete fragments of circulation core diagram, scattered side-by-side across many of the sheets. Each is drawn, redrawn, tweaked, abandoned and superseded. Some eventually appear in a plan arrangement for a particular scheme, only to be suspended – temporarily obsolete – by a new organisational direction.

The repertoire of formats explored across the pages begins with the fairly straightforward superimposition of a lozenge-shaped core into various plan configurations, then as a centrality to which rooms are attached. The centre of gravity shifts off-centre and back again. Small linking corridors appear and disappear. The circulation becomes more object-like, its form more sculptural as it gathers up certain programmes within its extent – a kitchen, dining room and bathroom – before receding to a compact volume; at first cruciform, then L-shaped, then off-set. The arrangement of rooms around this tight nucleus take on a more pinwheel format; sometimes dense, sometimes outward reaching. The core is revised as a circle within a square, then, inexplicably, the core is stretched into a street-like corridor with room-volumes loosely strung along its length. The circular core returns, but now as the centre of a dissected cluster of unevenly pizza-slice-shaped accommodation. The amoeba-shape comes back and soon retreats, as does the compact core and pinwheel of rooms. Finally, a hybrid appears in a small measured drawing: an eccentrically sub-divided circle at the centre of a box.

Despite what might read as a somewhat erratic sequence of experiments – and a curious meandering through Cubism, De Stijl and Constructivism – the fundamental idea of the project is never far from sight: the delineation of circulation as an autonomous and sculptural architectural event, capable of supporting a wide range of discrete programmatic volumes, extending from this structure over time. An expandable house.

To this end, Gowan is doing something quite sophisticated. He is taking this basic strategic idea, imagining a variety of formats that align with its conceptual basis, and exploring the potentials and limitations of the sub-formats that exist within each format. He is not starting from a number of wildly different positions – he never strays from the primacy of circulation as the stable and characterising infrastructure in each study – but instead acknowledges that a range of architectural outcomes are possible within such a strategy, each with the potential of giving clarity and legibility to that strategy from which they originate.

Showing

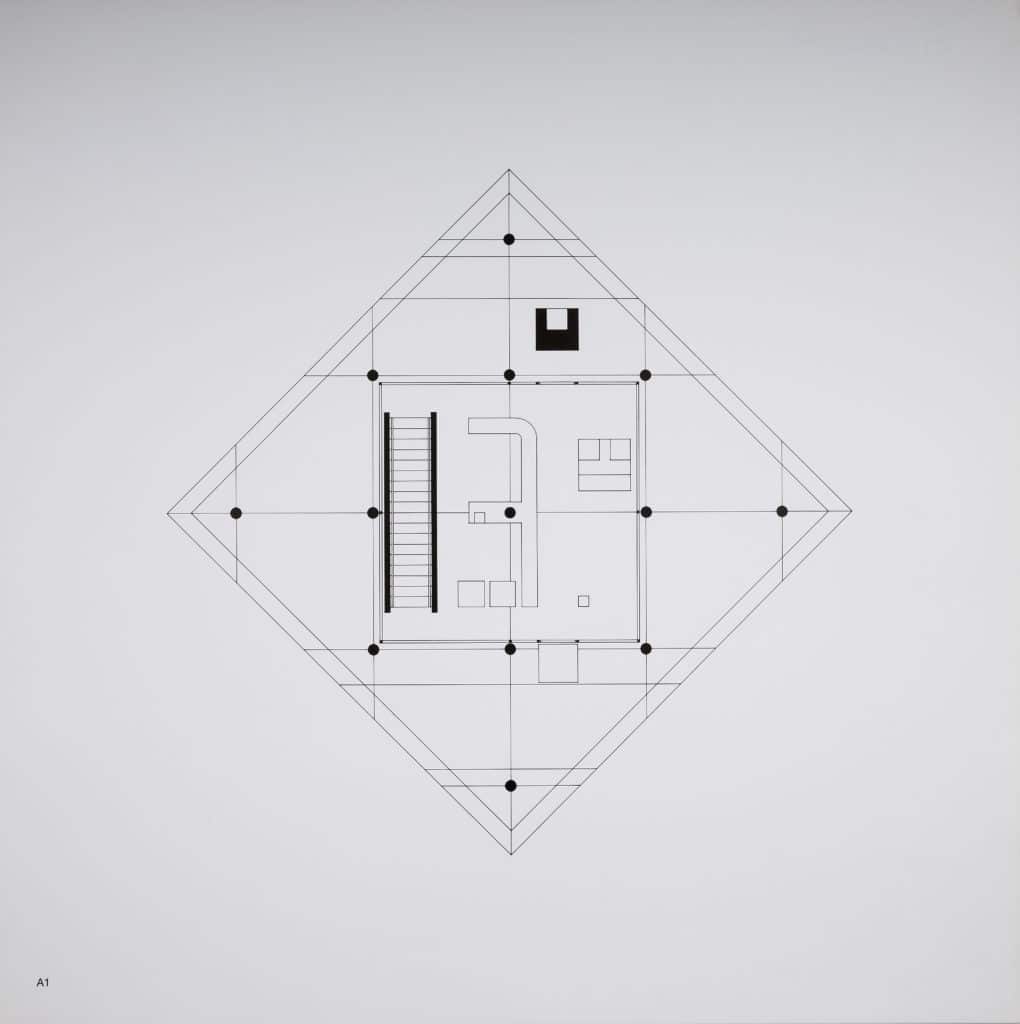

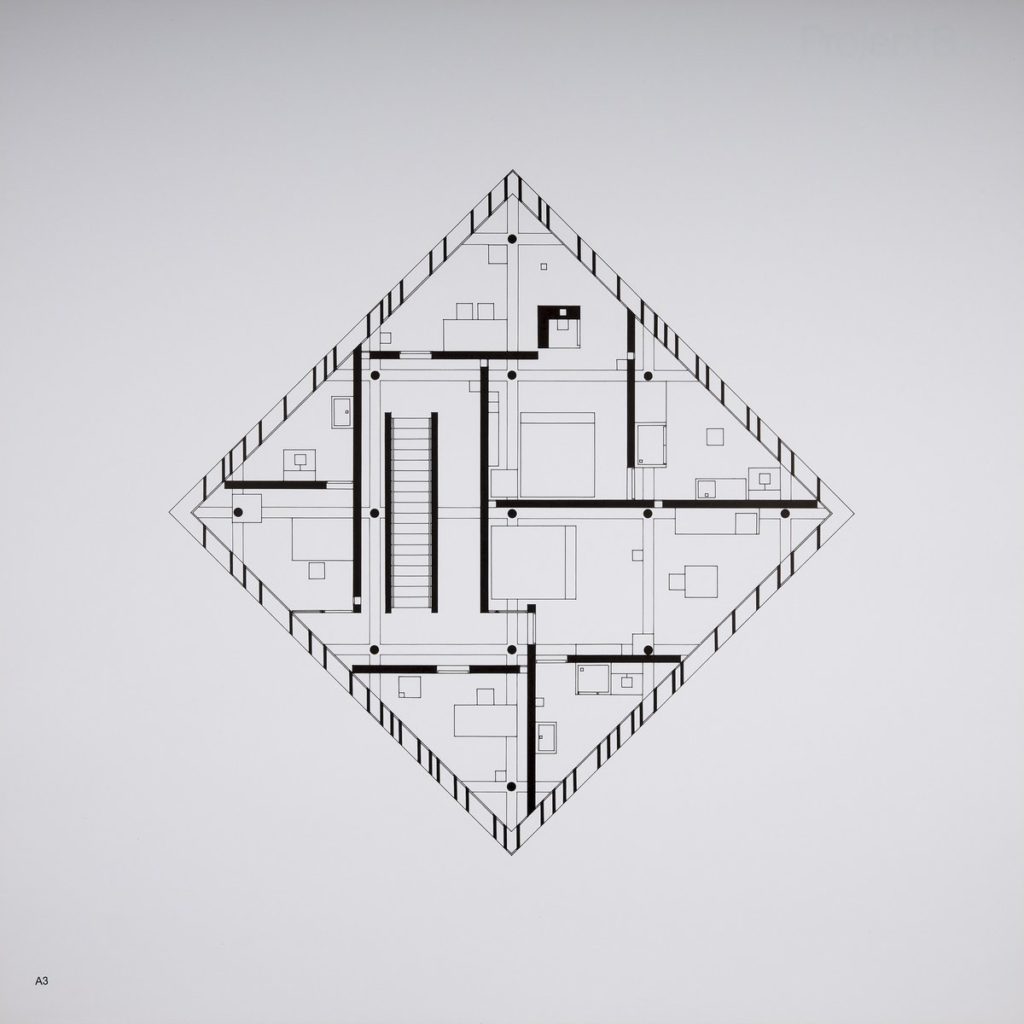

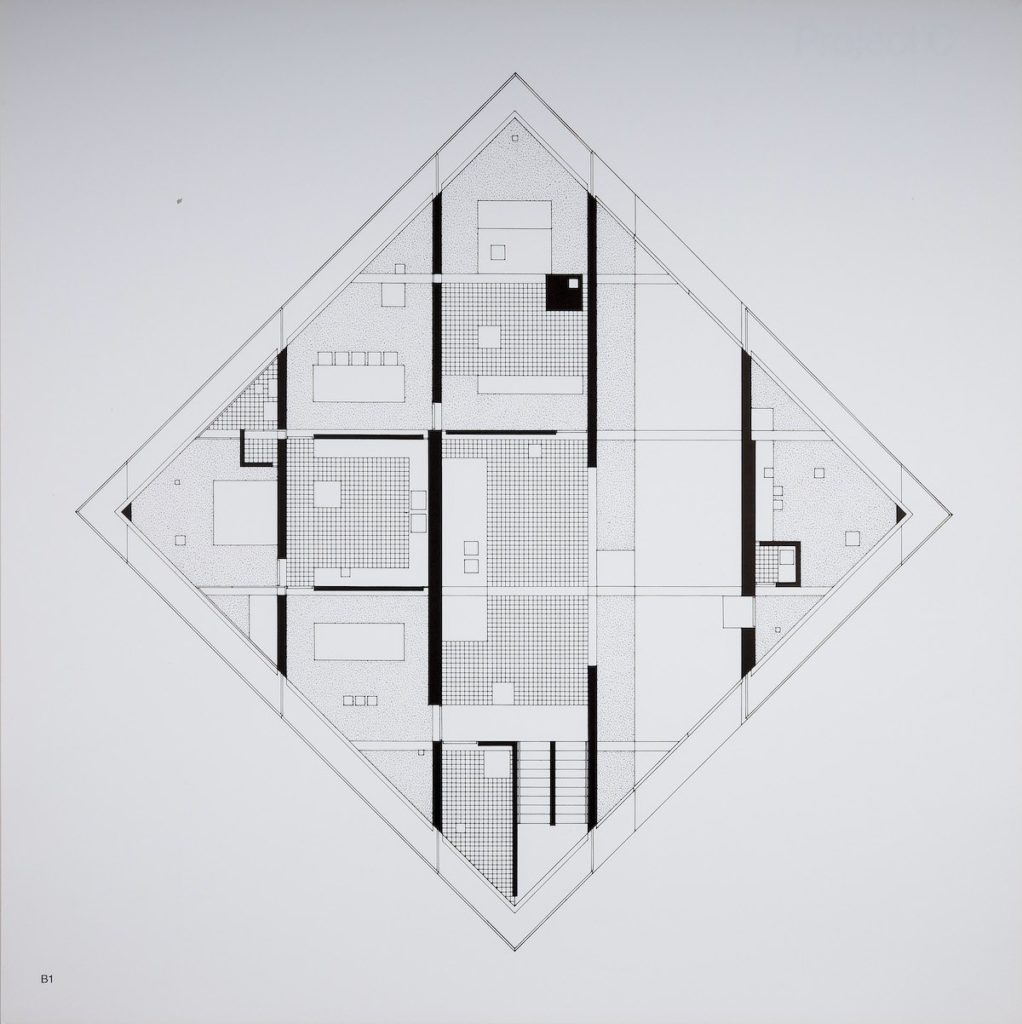

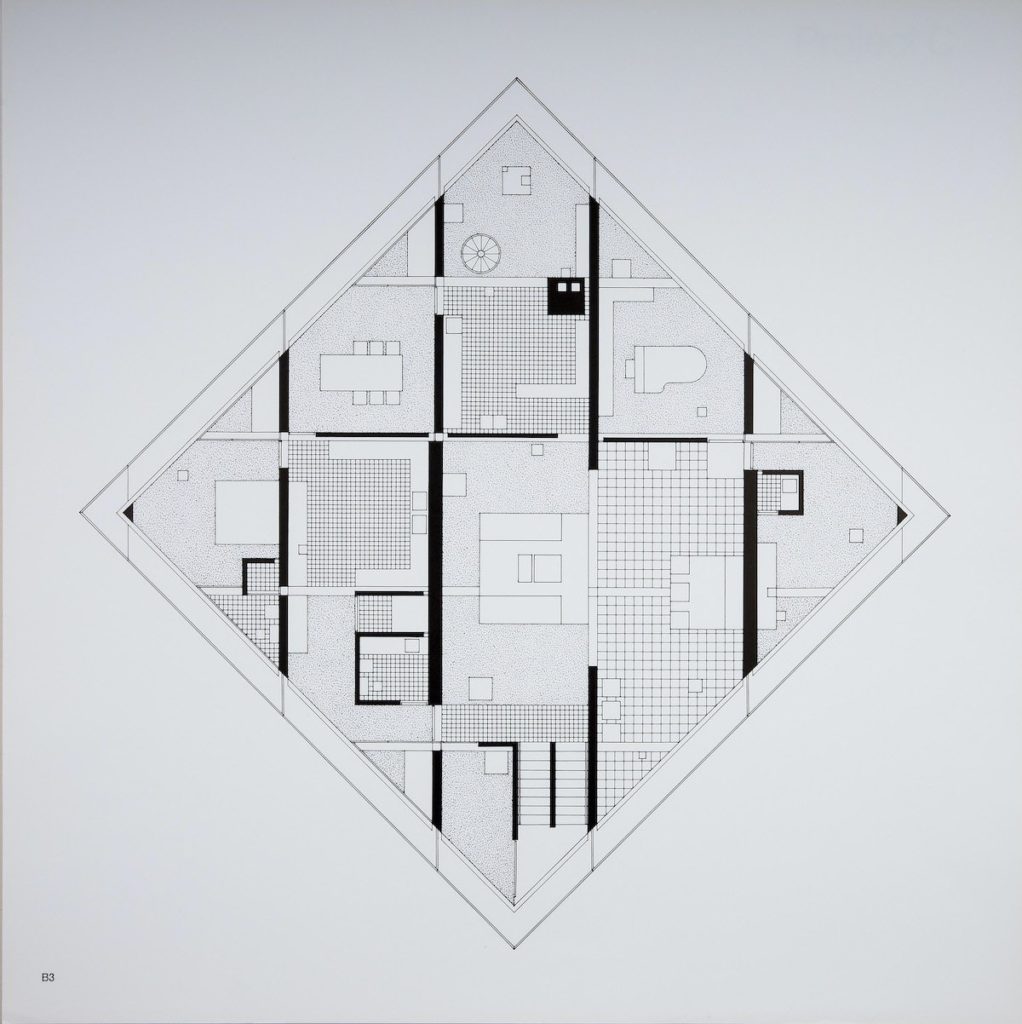

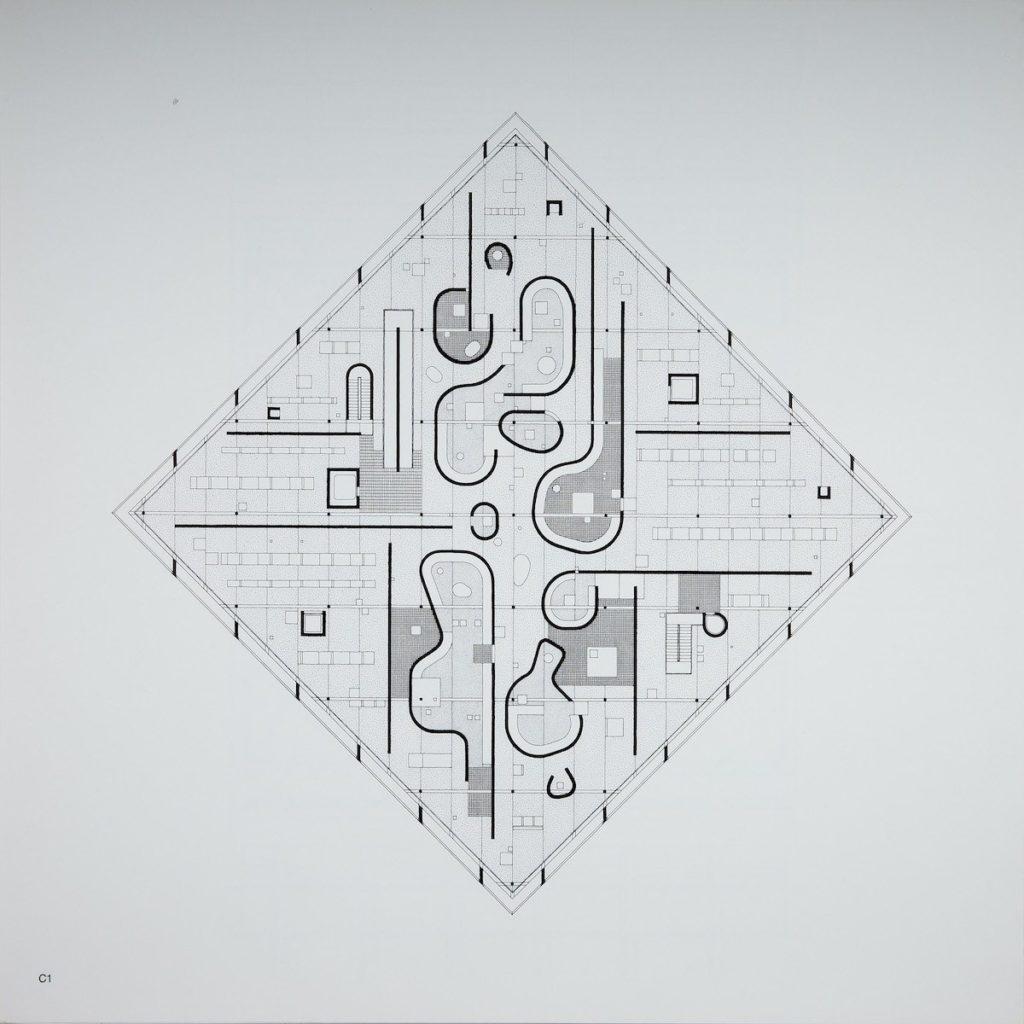

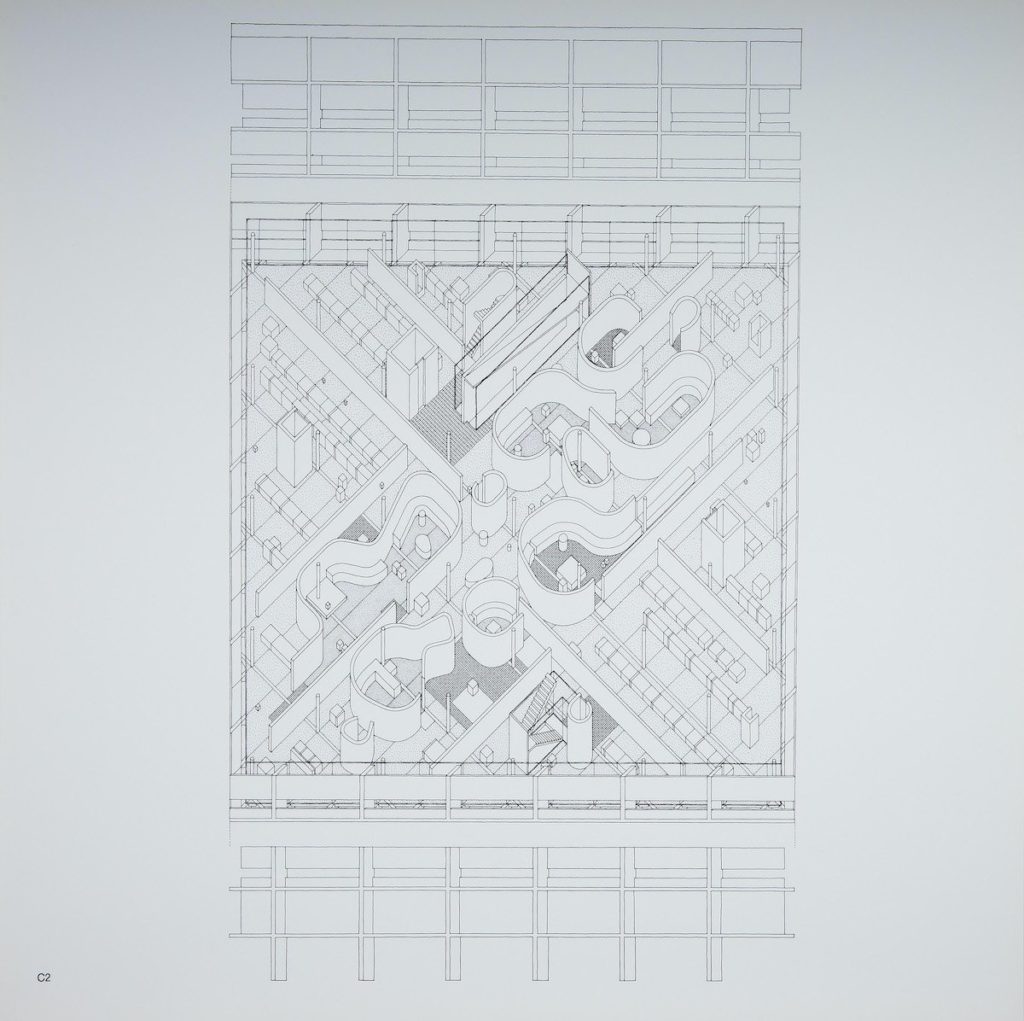

The notions of origin and variation mark an intersection between Gowan and Hejduk’s projects. The Three Projects – Project A. House, Project B. House and Project C. Museum – or The Diamond Thesis, has become an archetype of the variations-on-a-theme exercise. The basic premise is extremely simple: turn a square by forty-five degrees but retain its x and y axes parallel and perpendicular to the original orientation, setting-out a diamond in plan. The work then unfolds as a highly idiosyncratic study of a formal and spatial vocabulary both implied by the format, and capable of sublimating it. From this arbitrary first move, as Hejduk describes it, architectural potential is derived from the process of transcribing habitable programmes into the format:

The problem of point-line-plane-volume, the facts of square-circle-triangle, the mysteries of central-peripheral-frontal-oblique-concavity-convexity, of right angle, of perpendicular, of perspective, the comprehension of sphere-cylinder-pyramid, the questions of structure-construction-organization, the question of scale, of position, the interest in post-lintel, wall-slab, the extent of a limited field, of an unlimited field, the meaning of plan, of section, the meaning of spatial expansion-spatial contraction-spatial compression-spatial tension, the direction of regulating lines, of grids, the forces of implied extensions, the relationship of figure to ground, of number to proportion, of measurement to scale, of symmetry to asymmetry, of diamond to diagonal, the hidden forces, the ideas of configuration, the static within the dynamic, all begin to take on the form of a vocabulary. [1]

All that from turning a square by forty-five degrees.

Whilst Gowan searches for a configuration that is both contiguous and resonant with the conceptual intentions – for architectural clarity through the tailoring of form and format to an overarching idea – Hejduk’s iterations are an exploration of the potential within a self-imposed limitation; the elaboration of architectural ideas from a circumstance. The studies feel somehow close to the use of improvisation in music, wherein an intuitive idea or motif is explored over a relatively simple structuring convention, as both the vehicle and context for invention. Further, whereas Gowan’s sketches are studies sitting behind a project, Hejduk’s improvisations are the project.

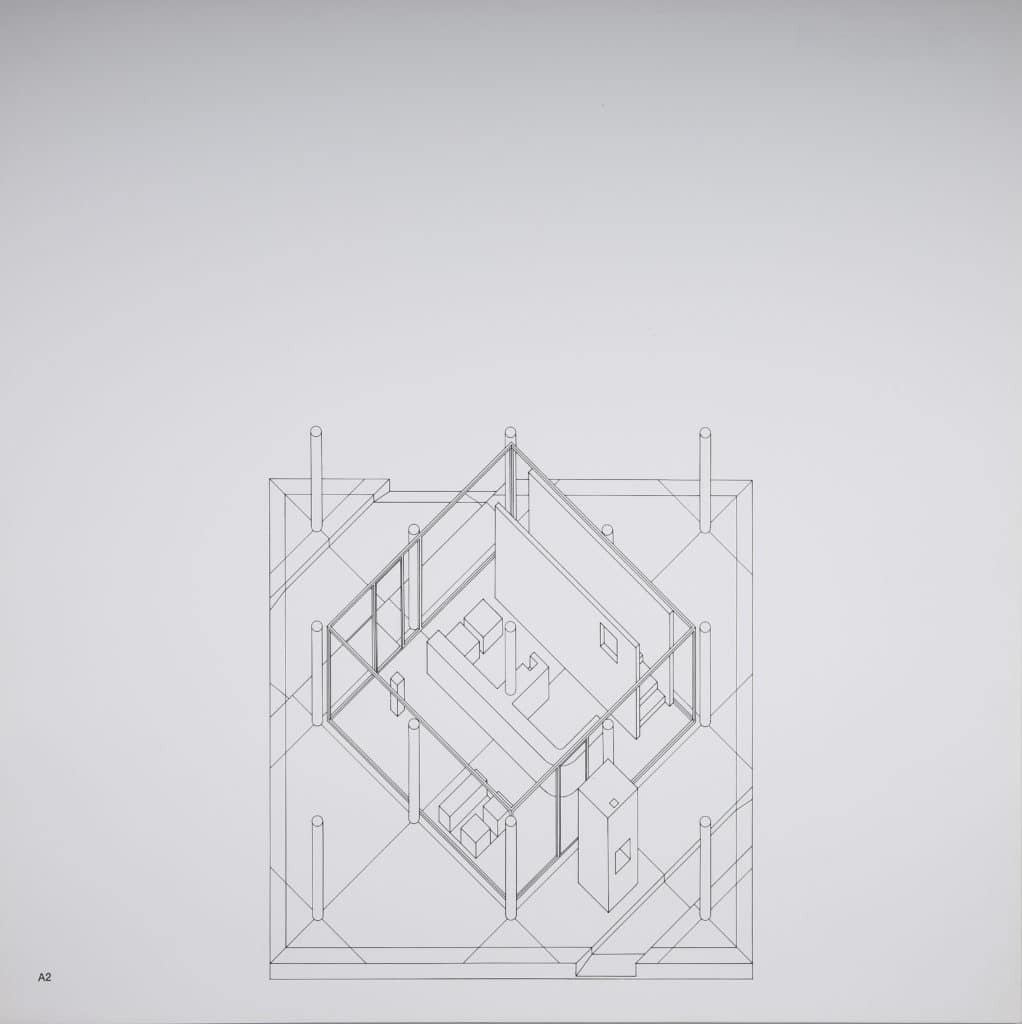

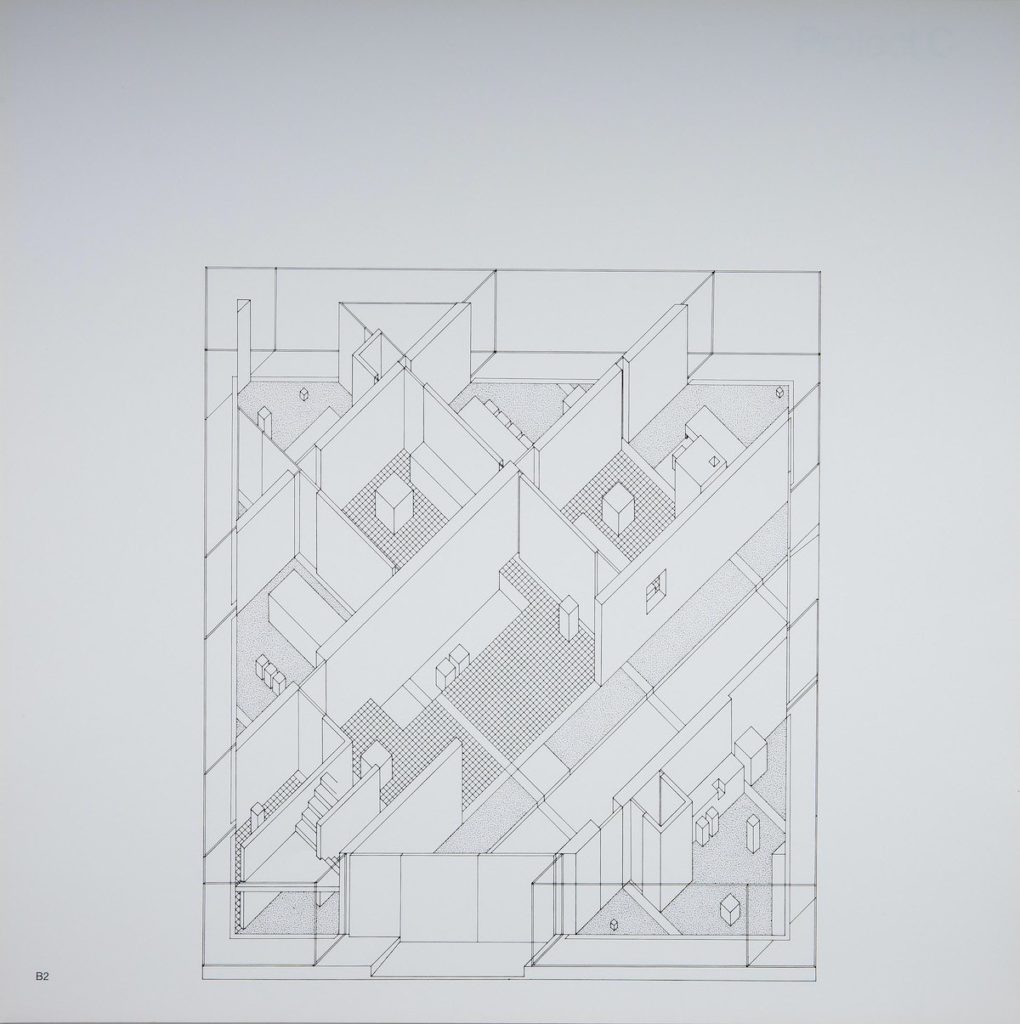

The drawings that make up this thesis unfold over twenty-four plates (excluding texts) containing a methodical sequence of plan and isometric projections per floor – eleven plates for Project A (including a model photograph), eleven for Project B (including a colour plate), and just two for the museum described in Project C.

The role of iteration is two-fold in The Diamond Thesis: the specific spatial adjustment of a limited set of devices across floors within a single project; and the thematic development across the three projects. There is a clear succession in both the application and articulation of columns, linear walls, curvilinear walls, stairs and chimneys from study to study. The arrangement of space within each oscillate between enclosure – via compartmenting, subdividing or enveloping – and the landscape-like openness of the floor-field that the architectural elements inhabit.

Project A evolves into Project B. The first remains intact and valid in its own right, but also becomes an object of critique and reflection for the second. Project C follows suit, but expands both the scale of the plane, and the complexity and audience of the programme. The means used to shape domestic spaces are reviewed and adapted to organise a collective territory. The promise of an interior landscape suggested in the first two houses reaches its fruition in the expanded topography of the final project. Beyond the hereditary and evolution of an idea, the conclusion to the thesis demonstrates that certain ideas can transcend scale and context through the precise modification of means to circumstance and intentions.

Unusually, in the context of other more reclusive intellectual exercises of the time, The Diamond Thesis supplements the exploration of formal and spatial vocabulary with a concern for physical reality and lived experience. The small text introductions that accompany each project concisely describe construction strategies, structural grids, ceiling heights, the spatial distribution of colours relative to eye level, and the mix of accommodation per floor. More enjoyable still are the implicit scenarios of use suggested by the specific relationships between openings, structural elements, partitions, circulation and furniture in each plate. True to the conventions of architectural plan drawing, the furniture in particular fills the studies with life – albeit somewhat esoteric on close examination (it pays to direct some attention to the relationships between chairs and tables, for example). Ultimately, each of the thesis projects result in the delineation of a place – perhaps not conventional, but a place nonetheless – organised with intelligence and wit.

Whilst obsessive in their repetitive scrutiny of principles, they offer much more than isolated geometrical experiments. They contain an enthusiasm that sets them apart from the dry academicism or tormented angst common to similar exercises. As Hejduk noted, the decisions made in each project employ ‘the intellect not as an academic tool but as passionate living element.’ [2]

Working

Gowan and Hejduk’s examples demonstrate the capacity for richness instilled in iterative work. They illustrate the potential for the rigorous and concentrated interrogation of ideas through drawing not only to add depth, but also to take a project in unpredictable directions; to places that would not be reached without such work.

In practice, architectural work contains many things. The majority of our time is dedicated to activities that establish the conditions for a good project: meetings, correspondence, administrative tasks, and the search for specialist knowledge to supplement our (happily) generalist position in the overall scheme of things. The successful marshalling of these – and other day-to-day complexities of professional life – might result in the delivery of a good-quality service or, with a mix of luck and talent, a decent enough building. It does not, however, guarantee that the outcome will be architecture.

It takes another kind of work to make architecture.

It takes a deep engagement with the making of a project; necessitating a critical sensibility, a sense of curiosity and an openness to the adventure latent in every commission. It requires both a lightness of spirit and a seriousness of intent on the part of architects: in themselves, their attitude to the world and their attitude towards their work.

You only get out what you put in. It therefore doesn’t seem too far-fetched to suggest that the pleasure experienced in architecture is directly proportionate to the pleasure invested in architectural work. Alejandro de la Sota once suggested that ‘if we don’t do it with joy, it’s not architecture. That joy is precisely what architecture is: the satisfaction that one feels’. [3]

By engaging rigorously with architectural work – looking, thinking, talking, drawing and making; over and over again, in an insistent and impassioned search for clarity and generosity – it seems possible that the outcome, no matter the circumstances or style, can be elevated to the status of architecture. That is to say, as in the examples described here, it will have been invested with the enthusiasm of ideas.

Notes

- John Hejduk, ‘Three Projects’ (New York: The Cooper Union, 1969).

- Ibid.

- Quoted by Alejandro de la Sota Jr, during the conference ‘Reflections on Alejandro de la Sota: A Pioneer of Modern Architecture in Spain,’ organised by Docomomo UK (London: RIBA, 27 November 2018).