Liquid Paper

In The Praise of Hemp-Seed, John Taylor – the self-styled Jacobean ‘water poet’ – at one point asks why poets have never sung the virtues of the plant before. It is, he answers himself, because their words run dry in the face of the limitless goods it brings – ‘the poets know their insufficience is’, he writes:

That were earth Paper, and Sea inke, they know

’T were not enough great Hempseeds worth to show.

Indeed, Taylor works hard to convince his reader that hempseed is almost everything, or at least that almost everything in some way depends upon it. And so, he expands upon the consequences of sail cloth, cordage, thread, clothing and, most of all, paper, in a world-engirdling panegyric that encompasses navigation, trade, the arts, learning, memory and religious enlightenment. As he proudly declares in the dedication that prefaces his poem:

I have (as it were) extracted oyle out of steele, and wine out of dry chaffe. I haue here of a graine of Hempseed made a mountaine greater than the Apennines or Caucasus, and not much lesser than the whole of the world.

In Taylor’s thinking there is a delight in liquidity and in the possibility of extracting something fluid from what otherwise seems unpromisingly dry – or alternatively of fertilising what is arid through insinuations of wetness, which might itself be a description of writing, one suggested by Taylor’s idea of a paper earth and an inky sea, the latter irrigating the former as it spreads across the surface. At the same time, Taylor is alert to processes of becoming wet and of drying out, and he knows that dry things may once have been watery and can still carry the trace of that state within them.

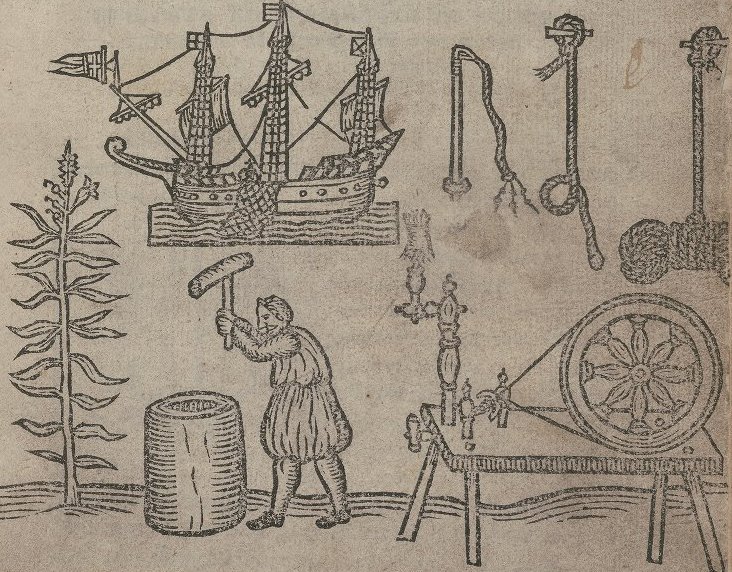

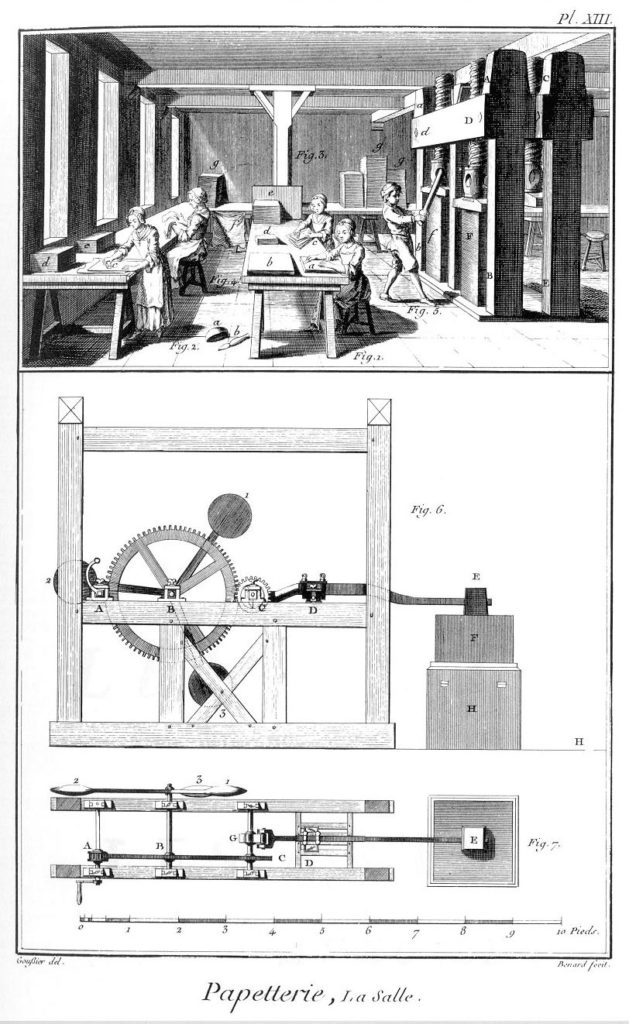

Today paper comes to us as the emblematically new material, so much so that the proverbial ‘blank page’ is a byword for what is unmarked, pristine and non-historical. No doubt the tendency to see it this way is reinforced by modern manufacturing methods and its production from wood pulp. But this was a very late development and until relatively recently the principal raw material for paper-making was rags (linen rags, though use of cotton increased from later seventeenth century) – old sheets, clothing, etc, with ropes and sails for poorer qualities of paper (hence the occupations of rag-pickers, rag-and-bone men, etc). The process involved sorting, washing the rags, soaking them in water until they began to ferment and come apart, and then pulverising them with mallets. The mixture of the resultant pulp of fibres and water was called ‘stuff’. This was contained in a warmed tank at which the paper-maker operated. He used a mould made from a wooden frame within which wires ran, and he formed the paper sheet by dipping it in to collect the fibres and gently shaking it to allow them to knit. This he passed on to a ‘coucher’ who allowed the water to run off, before setting the wet sheet on a felt. This went on until a ‘post’, usually 144 sheets, was formed, which was then compressed in a screw press to remove as much liquid as possible. The ‘layer’ or ‘layman’ removed the semi-dry sheets and pressed them again. They were then dried in a drying loft, and then sized – that is, given a glaze or coating – pressed again and dried again. Finally, their surface was smoothed as required (by rubbing with stones, by pressing, or by hammer), examined, and then dry-pressed once more. This procedure was not significantly mechanised until the 1830s.

For Taylor, this process – specifically the liquidity of this process – endows paper with a slyly subversive quality. Made from the rags of clothes, whose fibres have become mobile in their liquid suspension, it mixes society’s classes into ‘stuff’ (which is precisely what we call material shorn of classification) and, drying out, rebinds them together in a transformed way. As the literary scholar Adam Smyth has written: ‘Paper’s … remarkable quality is its material inconstancy: a sheet of paper has always been something else, and Taylor likes to think of this something else as a kind of ghost, a partially present other life’. Not only might the lowly come to be exalted by their afterlife in paper sheets that receive sublime verse, but in paper’s fabric ‘the Linnen of some Countesse or some Queene’ becomes ‘Mix’d with the rags of some baud, theefe, or whore’. Taylor, Smyth continues, ‘lingers over paper’s consolation: its muddling of hierarchies, its ironic blending of high and low, its whispered implication that things might be different’. Clothing’s return in the form of paper allows Taylor to taunt Puritans that the very things they wear might one day have damnable plays, or songs, or even Latin printed upon it:

And truely ’twere prophane and great abuse,

To turne the brethrene linnen to such vse,

As to make Paper on’t to beare a song,

Or Print the Superstitious Latine tongue

This sense of the ‘blank sheet’ as being far from blank, but multiplicitous and swarming in its constitution, endows a particular kind of value upon Taylor’s motif of a paper earth – notably he plays with the consonance of ‘reame’ (of paper) and ‘realme’ (the former just ‘an (l) too short’, a phrase that in turn seems to pun on ‘ell’, a measurement based on the forearm and hand and closely associated with cloth – as if it might just take a few more rags to effect the transformation of one into the other). Perhaps there is a hint here too of paper representing a kind of postdiluvian topography, of one that comes ‘after the flood’, in which distinctions have been flattened or washed away and their material expression turned to stuff – as the process of paper-making enacts every time, in its own limited way, a little visitation of the Flood.

Taylor, likely born in 1578, was by all accounts a colourful man – characterful, roguish, extravagant in both mirth and, to those who crossed him, malediction. As a Thames waterman, his profession was to ferry passengers from the north side of the river across to the theatres in Bankside and he seems on a number of occasions to have acted as the Watermen’s representative in court (in suits against the Players, seeking to prohibit the establishment of theatres on the north side of the river within four miles of the City; or against the use of hackney-coaches for journeys less than three miles). He was a crowd-funded author, financing through subscription his publications such as the Penniless Pilgrimage or Moneyless Perambulation – from London to Edinborough in Scotland, not carrying any money to or from, neither Begging, Borrowing, or asking Meate, Drink, or Lodging. It is likely that this long-distance walk was embarked upon in emulation – or perhaps parody – of Ben Jonson, who had set out on his own journey in early July 1618. Jonson held Taylor in low regard and complained of James I’s enthusiasm for the poetry of the ‘Sculler’. It seems they met in Leith, the port of Edinburgh, where, according to Taylor, Jonson gave him ‘a piece of gold or two and twenty shillings to drink his health in England’ – and presumably to send him on his way.

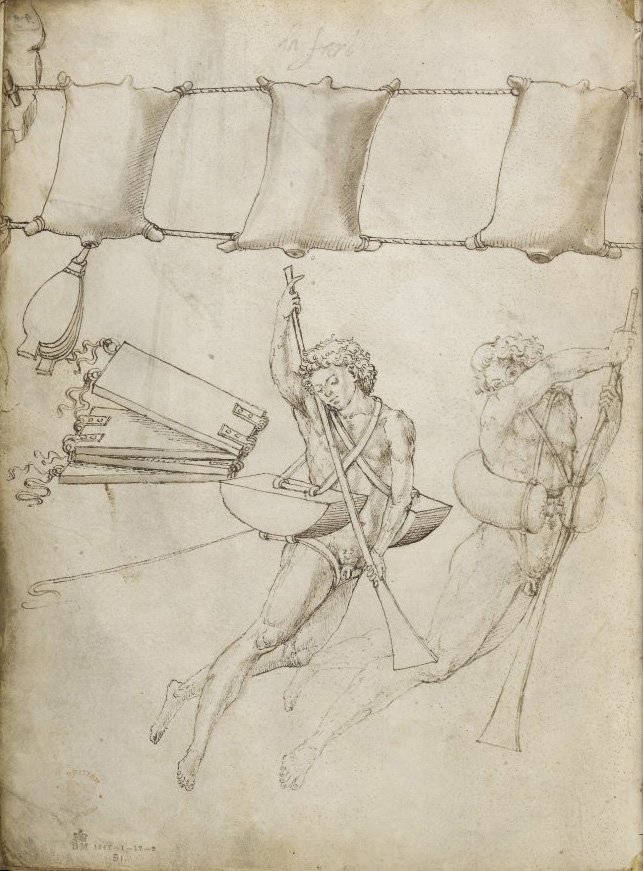

Taylor’s ‘The Praise of Hemp-Seed’ is a permeable work into which other things seep, including an earlier verse on a storm at sea (written ‘three years since’), a eulogy to Thomas Coriat, and an account of another journey he made – this time in 1619 along the Thames, when, for a bet, he rowed 40 miles downstream in a brown paper boat to the Isle of Sheppey, using oars whose blades were made of dried fish. For additional flotation he had eight inflated bullock bladders on board. These were blown up, he claims, by the breaths of eight different vagabonds, the sort likely to be hung on the gallows (the Homeric reference is clear – he describes these as winds in bags, similar to Aeolus’s gift to Ulysses). Taylor’s reasoning was that such thieves never die by drowning but dangle in the air at the end of a noose, and so their breath should endow a particular buoyancy, as if the water pushes it away:

For why such breaths as those it fortunes euer,

They end with hanging, but with drowning neuer ;

And sure the bladders bore vs vp so tight,

As if they had said, Gallowes claime thy right.

This was the cause that made vs seeke about,

To finde these light Tiburnian vapours out.

We could haue had of honest men good store,

As Watermen, and Smiths, and many more,

But that we knew it must be hanging breath,

That must preserue vs from a drowning death.

And so, despite their sodden paper boat being ‘bottomlesse as Hell’, Taylor and his accomplice – Roger Bird, a vinter – made it to Queenborough by the next morning. Feted by the mayor, who wanted to display the remains of their craft, they found on returning from their feast that the paper vessel had been torn by the townsfolk into little pieces, and that these they had pinned to their hats as – Taylor says – ‘reliques’. He writes:

…whilst we at our dinners thus were merry,

The Country people tore our tatter’d wherry

In mammocks peecemeale in a thousand scraps,

Wearing the reliques in their hats and caps.

That neuer traytors corps could more be scatter’d

By greedy Rauens, then our poore boat was tatter’d;

With this disintegration and recirculation, Taylor’s paper ship met, we have to admit, a suitably liquid end – even if it turned out to be one that took place upon dry land.