Space

Space in architecture is a special category of free space, phenomenally created by the architect when he gives a part of free space shape and scale. Its first two dimensions – width and breadth – are responsive mainly to functional imperatives in the narrow sense, but the manipulation of its third dimension – height – grants the inhabitant’s mind the special opportunity to develop yet other dimensions beyond.

Architects’ words seem to rile people. We talk of ‘making’ a space, and others point out that we have not made a space at all; it was there all along. What we have done, or tried to do, when we cut a piece of space off from the continuum of all space, is to make it recognizable as a domain, responsive to the perceptual dimensions of its inhabitants.

Curiously, the acts the architect can most effectively perform with space appear to be opposing ones, though both seem to work. You can capture space or let it go, ‘define’ it or ‘explode’ it, space is surely one of the few things that you have more of after you have ‘exploded’ it, but it seems to thrive in captivity too. The failures come when we don’t make it recognisable, when we do not distinguish a piece from the continuum.

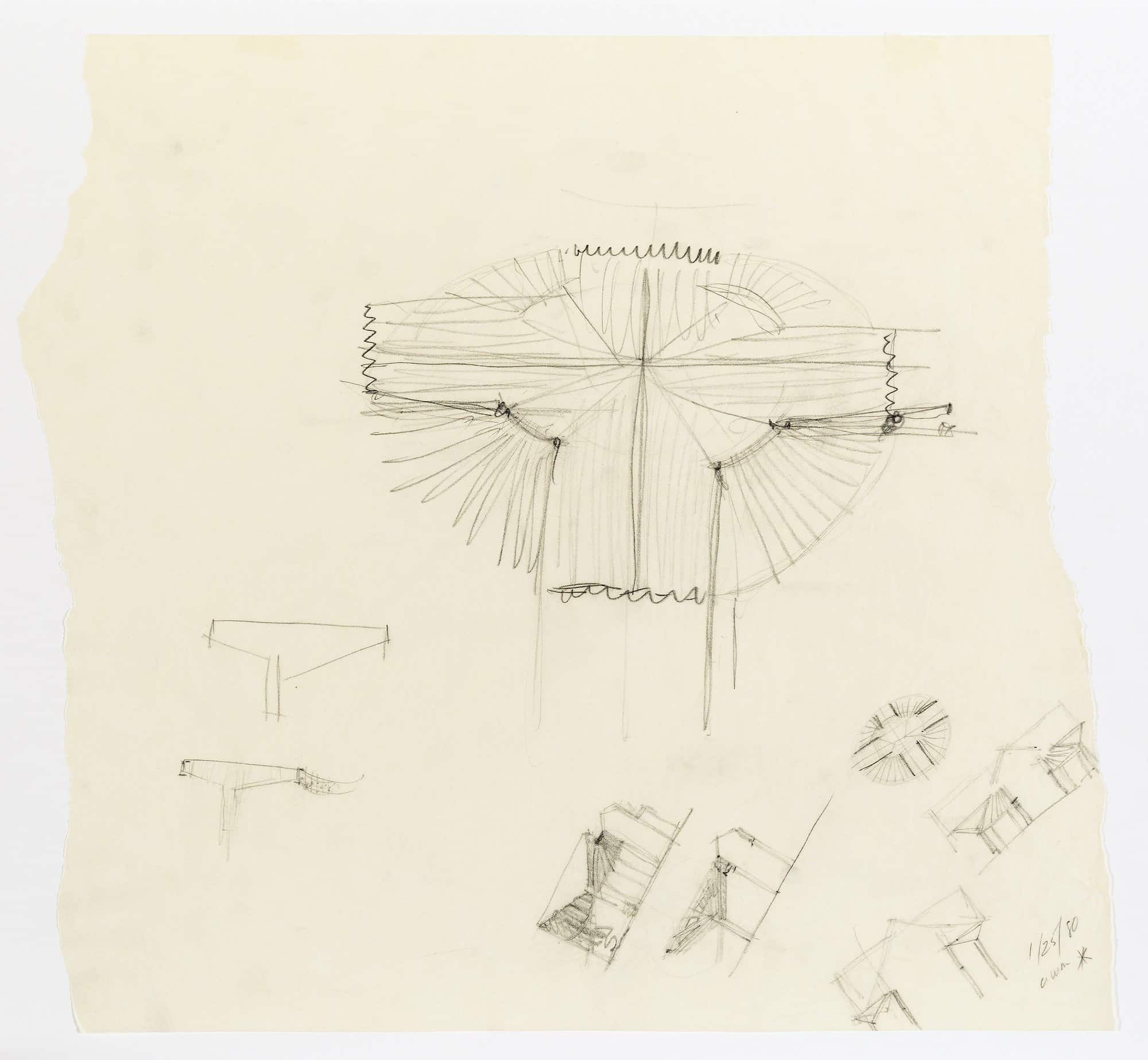

It is easy to see why we fail so often. For one thing, we do not draw space, but rather plans and sections in which the space lurks. So there is a constant temptation to focus on objects rather than on the architectural space they breathe into existence. Drawing-board victories (like getting everything lined up) replace and negate the real pleasures discoverable in space.

Architects’ spatial enthusiasms have been heterogenous during the past decades. The principles of the Austrian planner Camillo Sitte (rediscovered just after World War II and translated into English) were based on a fondness for medieval piazze, plazas, places, and plätze. Sitte stressed the importance of keeping their corners solid so the space could not escape. He was interested, too, in keeping the center of such spaces unencumbered by statues and other solid objects, so that the observer could stand there and feel that he was the center of a composition perceivable in its entirety. But the worst gaffe, as Sitte saw it, was to leave the corner open so that the space, no longer either contained or dramatically escaping, seemed to leak out and be lost.

Another great influence which has been present is an almost complete inversion of those rules. It lies behind the Baroque stage drawings of the Bibiena family and the architectural fantasies of Piranesi – especially his prisons, where ramps and stairs rise to mind-boggling distances in the almost limitless upper reaches of incomprehensible spaces. Yet another spatial construct has been found by Modern architects in the great mosque at Córdoba, where an orchard of columns fades into the dark distance and equivocates about the limits of the place and the position of spaces and objects in it.

Siegfried Gideion sought to reconcile (or fudge) these contrasting spatial enthusiasms by postulating, in sort of art-historical coda to Einstein’s theory of relativity, the presumption that architectural space since the seventeenth century had become linked with time. But it is difficult indeed to square his thesis with the static and repetitive design of most Modern buildings.

A much more surprising (and in the end illuminating) thesis is the one set forward by the contemporary Greek planner C. A. Doxiadis. It manages to jump clear of the Cartesian grid, which has so far contained most spatial arrangements, to discern in ancient Greek sites a radial organizing system. From the point of entry to a sacred area, 30-degree or 36 degree segments of a circle radiated. The corners of all buildings completely closed the view (in the Doric order) or opened a single segment to the surrounding landscape (in the Ionic order). Perhaps more important than the question of whether this was really the way the ancient Greeks did it, is the capacity of modern man to imagine such a system. It seems to be one of a number of signs that we, in our pluralism, are finally working clear of the rigid Cartesian grid, with its dictatorship of the right angle, by which Modern architecture has to be understood from the point of view of the person perceiving or experiencing it – not as a mathematical abstraction.

Another sign, reinforced by psychoanalytic literature, is the return of body-centered space. Psychiatrists have noted that as children we first perceive that up is different from down, and left from right, and that front is very different from hack. But as we grow up we are gradually disabused of the notion that the three spatial dimensions do have moral significance. Now, however, these archaic truths are once again beginning to be taken as the basis for organizing the space we pluck out of the continuum.

Again, space in architecture – whatever its organizing impulse – is of interest to us in only two ways: either because of its orderly containment or because of the drama of its escape. The pleasures of a serene and carefully proportioned contained space (like a Palladian double-cube room) can for us coexist with the excitement of a twentieth-century spatial explosion (like the U.S. Pavilion at Expo ‘67 or the Matterhorn at Disneyland).

Excerpted from Charles Moore, Dimensions: Space, Shape & Scale in Architecture (1977)