George Wilkinson: Building On The Stones Of Ireland

George Wilkinson (1813/4–1890) was an English architect employed by the Poor Law Commissioners in 1839 to facilitate the construction of workhouses throughout Ireland in response to growing numbers of homeless poor. While historians have written of the Poor Laws and the workhouses, Wilkinson’s contribution to both merits further study in light of his broader views on architecture, Irish civilisation and the prospects for a country in a time of famine. Of equal interest to his buildings, though generally overlooked, is a treatise he published in 1845, titled Practical Geology and Ancient Architecture, which reveals both Wilkinson’s philosophical and practical concerns.

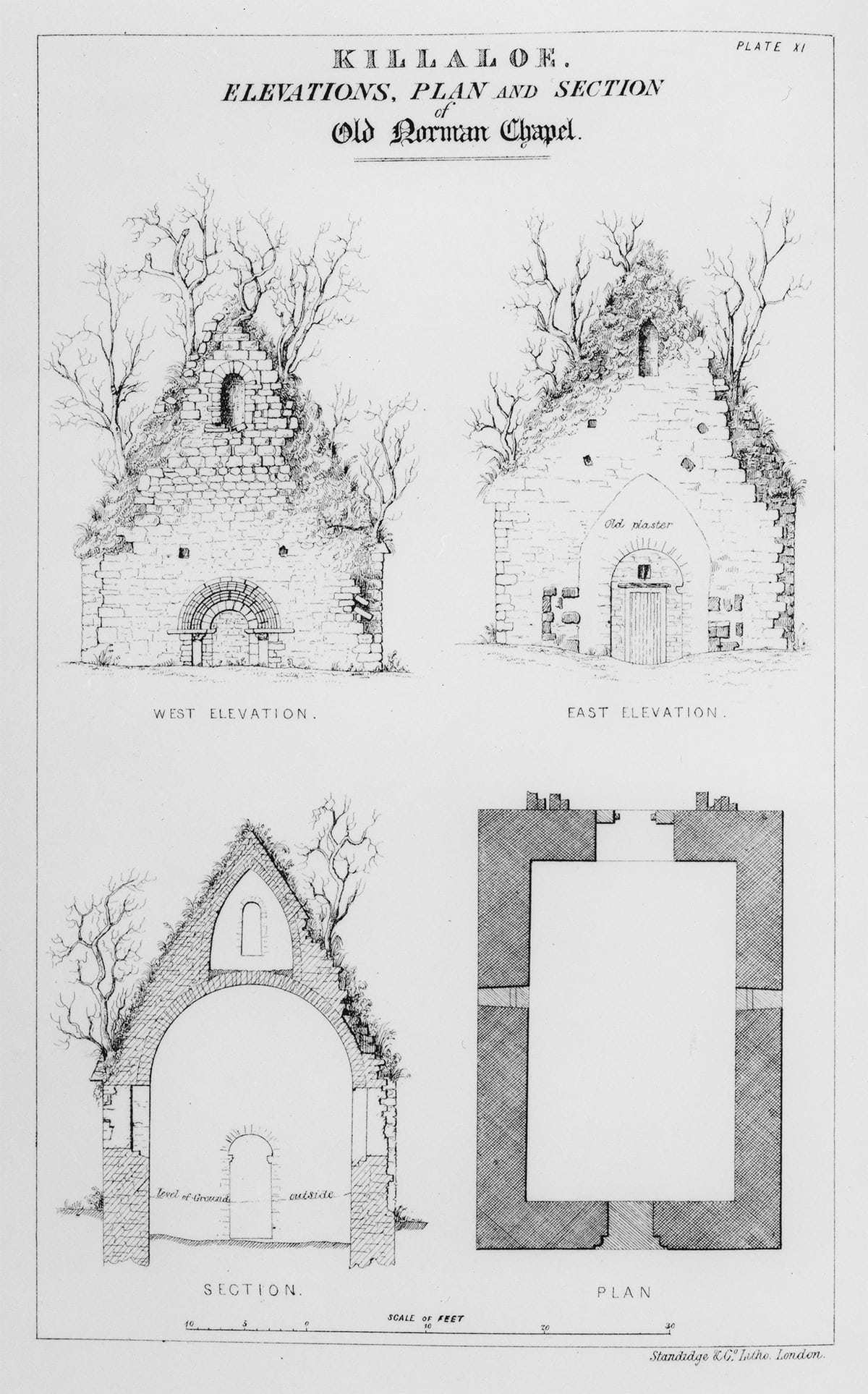

Of particular interest is the way that Practical Geology describes the character and integrity of the Irish by identifying them with the remains of old buildings their ancestors once inhabited or which were forced upon them by others like the Normans, the places in which these stood and the landscapes that provided stone for building them. In this manner its author encouraged architects to build structures that were solidly fixed in place — as many of Ireland’s pre- and early Christian and Medieval ruins appeared to be.

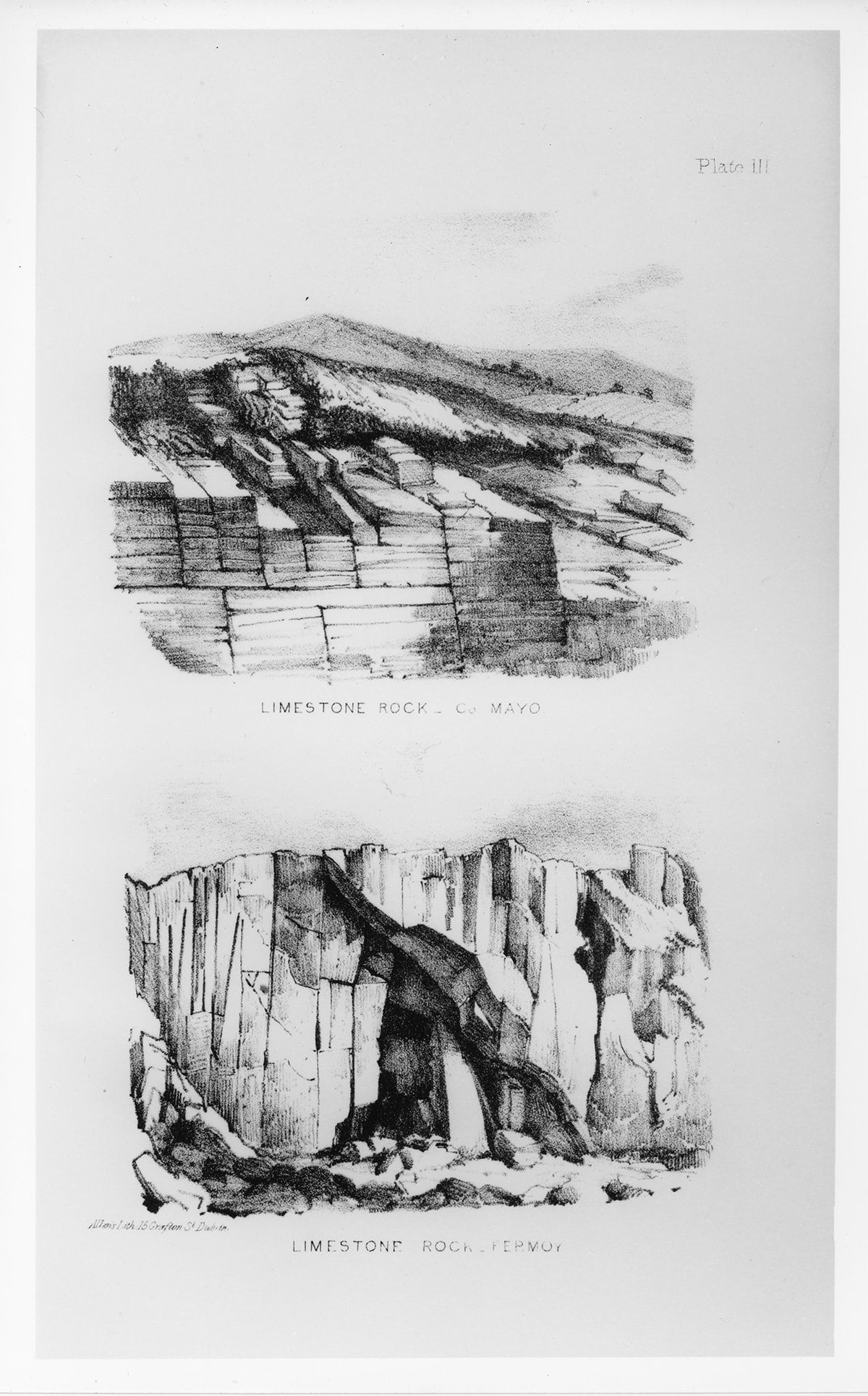

The text is mainly a work of ‘economic’ or ‘practical’ geology that surveys, county by county, the origins, stratigraphy and use of stone for building purposes at various times in the past. Much of the book is composed of detailed descriptions of the character of stones native to Ireland, their location, weight, absorptive and cohesive qualities, load-bearing capacities and resistance to fracture. Accompanied by illustrations of rock strata in situ and stones cut for masonry, readers are informed of differences in the appearance and performance of materials such as exist between the categories of igneous rocks used for building as opposed to sedimentary or stratified ones. They are told of the beautiful crystalline structure and durability of the former versus the layered appearance and workability of the latter.

Parallel to this rather prosaic commentary is another, more abstract one. Supported by illustrations of buildings of various ages Wilkinson made broad claims for the appropriateness of one or the other rock strata or masonry construction for the people who once had fashioned stone into houses, temples, churches and fortifications, their thoughtful and skillful disposition, character and way of life. Thus, Wilkinson introduced his readers to geologic time, though mainly to support speculation on human nature, specifically the suggestion that the people of Ireland, like the stones of Ireland, were themselves fixed in place or should be.