David Kohn Architects

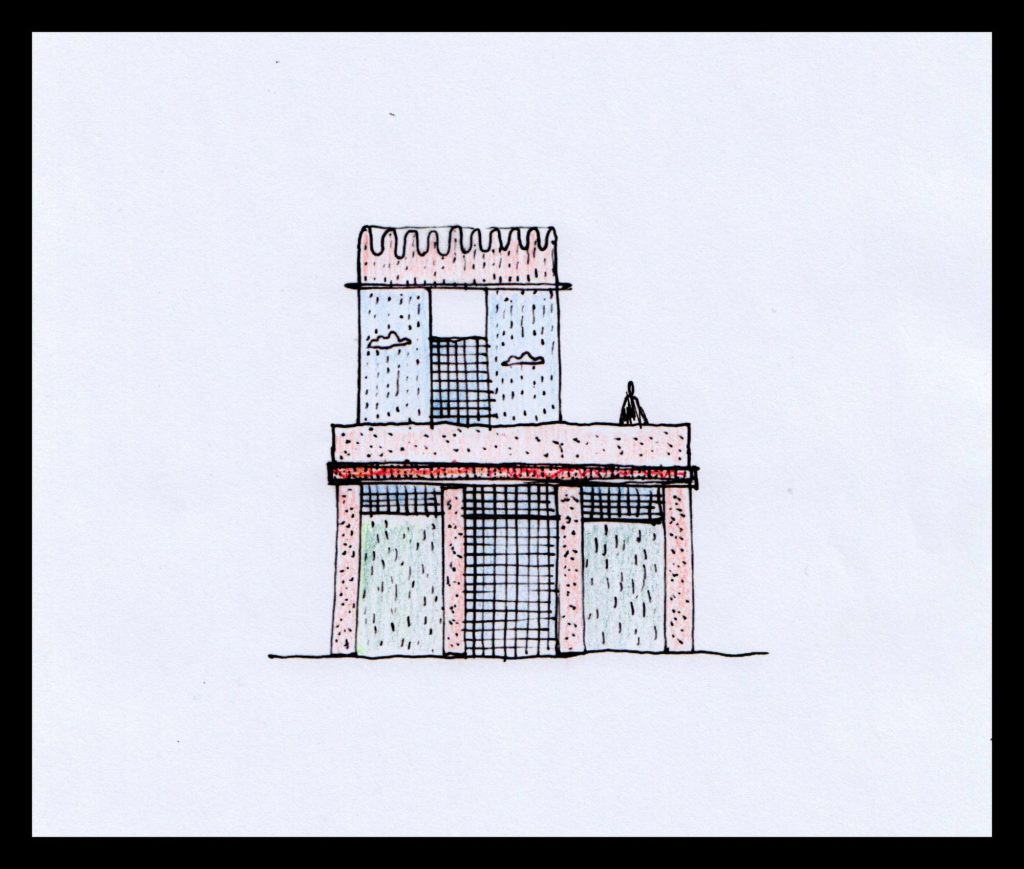

se two drawings of the Hounslow gate, however, belong to a different kind of drawing, which happens less frequently, possible only every few months. It often happens at a moment in the design process when progress is slowing, the range of issues we are exploring seems too restricted, a sense of playfulness too distant. Such drawings are made in isolation, on blank pieces of paper, usually after I’ve organised my week and then my desk. There’s a scale ruler and a Tipp-Ex pen involved; an expectation of precision, at least in terms of proportion, the hierarchy of parts and the role each element will play in the composition. The whole is sketched out lightly and the primary divisions follow. Then I will likely work through scales, from the bodily to the decorative, from texture to colour. Perhaps most importantly, the stages of the drawing reflect the range the architecture is expected to cover, the different scales, elements, technologies, materials, craftspeople and traditions.

Unlike the conversational sketches, these drawings are more like rhetorical statements. They describe wholes and not fragments. They anticipate being seen in isolation and without commentary. They establish the relationships between all the parts, and their usefulness is long-term. They might be relevant to a project for months and they might occasionally be relevant to a period of work within the practice spanning years. I feel uncomfortable starting them, I agonise while doing them and I feel tired when they are finished. Thinking about it, I can’t say I enjoy doing them that much.

Afterwards I feel relief and the occasional sense of achievement. The drawings’ relative structure and precision are reliable, their synthesis anticipates construction and therefore closure, their wholeness stands in defiance of discourses that claim architecture can be neither monumental nor autonomous. The contingency of the contemporary world is not reflected in the instability of the architectural form, but rather in the ambiguity of its symbols, the incongruity of its materials and the bathos of the hand-crafted surrounded by the machine-made. In their small way, these sketches assert contemporary architecture’s freedom to appropriate from history, to experiment with technique, to redefine what is sacred and profane. The constraint that the work imposes on itself is that it should be synthesised, that it should be whole and more than the sum of its parts.